As early as 1938, at the age of 21, long before he was a world-famous sci-fi novelist and scientist, Arthur C. Clarke published his essay “The Fantastic Muse”1 concerning fantasy and sci-fi poetry. The essay is short (885 words) and even then quotes extensively from Alfred Tennyson’s 1835 poem “Locksley Hall”, a speculative poem that Clarke extols as/for its ‘prophecy’ which is ‘more vivid every day’ (for Clarke was writing during the advent of WW2):

When I dipped into the future as far as human eye could see;

Saw the Vision of the world, and all the wonders that would be.

Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales

Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rained a ghastly dew

From the nation's navies grappling in the central blue.

The other principal aspect of speculative poetry Clarke considers in his essay, particularly with reference to John Masefield’s revelatory poem “Lollingdon Downs” (1917), is the superior quality of its ‘picture’, which ‘has never been excelled by the authors who have specialised in describing such happenings [since] It gives a better description of astronomical space th[a]n pages of text-books could.’ For Clarke, then, there is a visual, visionary and experiential evocation produced by the best speculative poetry that cannot be matched by more prosaic science writing.

Just one year later, in 1939, Clarke published his Science Fiction poem “The Twilight of a Sun” in The Fantast magazine, the penultimate lines of that poem quoted on the magazine’s cover2:

For some day our vessels will ply

To the uttermost depths of the sky

Those with a knowledge of Clarke’s later science fiction novels, particularly Against the Fall of Night (1948 and 1953) rewritten as The City and the Stars (1956), may appreciate just in the poem’s title his perennial themes or moods of ‘deep time’ (the ancient dying sun) and being ‘haunted’ (by a lost or past civilization). In addition, critics are still struck by the ‘poetic’ and picturesque quality of Clarke’s novels and writing style3.

Despite the above, we should not forget that Clarke did produce the seminal ‘science’ writing that was the non-fiction book The Exploration of Space (1951), closely followed by Exploration of the Moon (1954), the latter used by Wernher von Braun to convince President J.F. Kennedy that our moon was reachable. Yet it was with the publication of the first title that Robert A. Heinlein and Clarke began writing to each other: Heinlein’s first novel, Rocket Ship Galileo (1947), had initially been rejected by publishers because going to the Moon had been considered far-fetched(!), Heinlein then going on to write the screenplay for Destination Moon (1950).

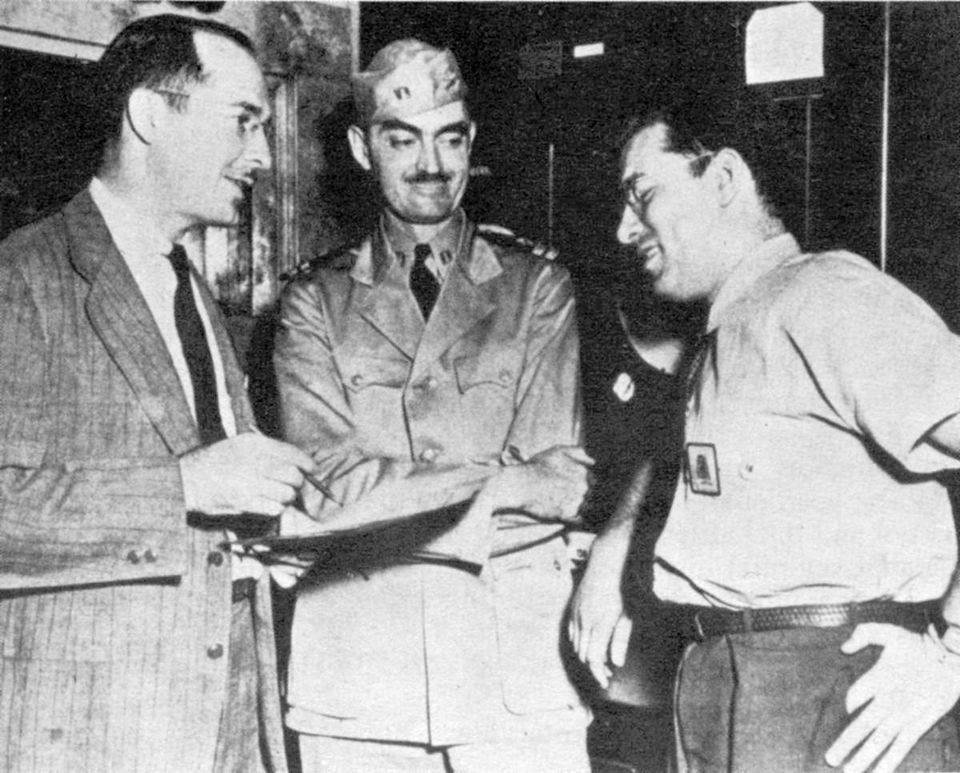

The two met in person in 1952 and remained on friendly terms over the decades, visiting each other in the US and Sri Lanka (Clarke moving from the UK to that island in 1956), despite some differing political views. Heinlein and Asimov both began publishing in Astounding Science Fiction magazine in 1939 and were subsequent colleagues at the Naval Air Experimental Station during WW2, although their relationship was sometimes fractious in terms of both personalities and politics. Thus, Clarke, Asimov and Heinlein became informally known as the “Big Three”, the trio credited with bringing science fiction into its “Golden Age”4.

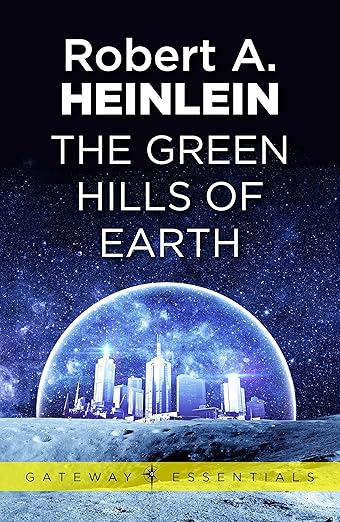

Heinlein produced very little poetry, but he did see three speculative poems, “The Hills of Earth”, “The Grand Canal” and “Jet Song”, published in his sci-fi short story “The Green Hills of Earth” (1947). It is the moving story of Rhysling, ‘the Blind Singer of the Spaceways’. To quote one critic, ‘This involves Robert A. Heinlein smoothly writing poetry in several styles, making it look as easy as his prose, casually at home in our future’5. The Rhysling crater on our moon was named by Apollo 15 astronauts, who quoted the last verse of Heinlein-as-Rhysling’s “The Hills of Earth” as the third Apollo 15 moonwalk was ending6:

We pray for one last landing

On the globe that gave us birth;

Let us rest our eyes on fleecy skies

And the cool, green hills of Earth.

Nor should we forget that it was Heinlein who either coined or popularized the term “speculative fiction” with his 1947 essay “On the Writing of Speculative Fiction”. He advocated for the term “speculative” to be used to encompass the genres of science fiction, fantasy (these first two genres referred to fairly interchangeably in Clarke’s 1938 essay) and other related genres (today, these tend to include horror, the weird and the Gothic). In his own essay, Heinlein defined two key elements of speculative fiction: the part ‘about people’ and the part ‘about gadgets’. It was also Heinlein who identified the ‘What would happen if–’ dynamic or principle that, even today, instigates or underpins the speculative. For all that Heinlein’s essay still carries a particular authority, however, he opens his essay by quoting Rudyard Kipling and referencing a poetic literary tradition rather than a short story or novelistic one:

There are nine-and-sixty ways

Of constructing tribal lays

And every single one of them is right

It suggests Heinlein himself was wary of being overly prescriptive or definitive, perhaps understanding that to be so convergent was at odds with the divergent and evolving nature of the speculative, a tendency that implicitly undertakes explorative and creative research in order to (and only in order to) break new ground (and provid e an original vision and contribution to knowledge). It also strongly suggests that Heinlein understood the nature of the speculative as extending to older traditions, other cultures, ideas and forms beyond the short story and novel-based concerns and interests of his own essay and Western constituency.

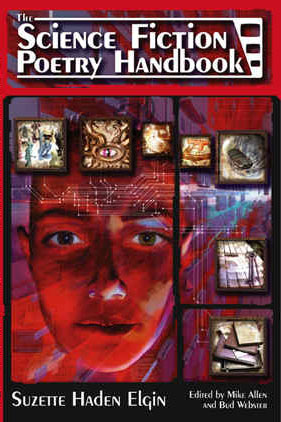

Significantly, the blind ‘bard’ Rhysling is described as ‘part […] Rudyard Kipling’ in Heinlein’s story, the novelist and poet Kipling (1865-1936) growing up in (British) India, with that culture and its traditions informing a great deal of Kipling’s fantasy-oriented output. Just as Clarke and Asimov look to Tennyson for a defining exemplar of sci-fi poetry, then, so Heinlein repeatedly looks back to Kipling for defining exemplars of speculative fiction and poetry. All of the “Big Three”, though, understand the speculative value of looking back in order to increase understanding and make progress going forwards, just as Rhysling keeps striving to go forwards to arrive back home finally. Indeed, it is in just such a spirit that this “retrospective” is being written for the Science Fiction Poetry Association (SFPA) and its members, the Association founded by sci-fi writer Suzette Haden Elgin in 1978 that presents the annual Rhysling Award for speculative poetry.

Elgin’s first sci-fi story was “For the Sake of Grace”, which appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1969, and was then incorporated into her novel At the Seventh Level (1972), a thematic forerunner to Margaret Attwoood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) in that both novels describe dystopian patriarchies. In Elgin’s novel, the only profession open to women is Poetry, the study of poetry a religious calling which sees its students the most honored members of society. For Elgin, the self-empowering pursuit and study of poetry literally instigated her wider writing and, arguably, some of her own social progress, a progress she looked to share via a wider enlightened community: the SFPA.

In 1999, Elgin published the essay “About Science Fiction Poetry”, available on the SFPA’s site, offering critical reflections on the lesser ‘value’ generally ascribed to science fiction poetry when compared to science fiction short stories and novels. Elgin rightly identifies that ‘The definition thing is a monstrous barrier’, and relates why she proposed that ‘an sf poem was one that had two parts: a science part, and a fiction – narrative – part.’ She then tells us that ‘the sf poets shouted me down in short order’, but finishes by supplying two of her own poems that might make her case as/by speaking for themselves. Then, in 2005, Elgin published the highly comprehensive and extremely useful Science Fiction Handbook (also available via the SFPA website). Chapter One tackles the same old ‘monstrous barrier’ as before, but now ‘speculative poem’ is understood as an ‘important term’ and ‘the most popular cover term […] commonly used to include all four of the other [genre] labels.’ Also, we now have an expansion on before, because ‘my personal definition for the science fiction poem itself has three [my emphasis] parts:

- A science fiction poem must be about a reality that is in some way different from our existing reality.

- It must contain some element of science as a part of its focus.

- It must contain some element of narrative – some “story” element.’

Once the monstrous has been laid (largely) to rest, the handbook is freed to turn to five chapters of exemplar poems for different aspects of the craft. In a similar vein, the closing two sections of the handbook provide an extensive reading list of exemplar poetry and a full record of the winning poems of the Rhysling Award, each an exemplar in their field, naturally.

And surely that is exactly as it should be, yes? Speculative poetry should be able to speak for itself. Once a reader appreciates a number of exemplar speculative poems, then surely they begin to appreciate what speculative poetry truly is. And the more they read appreciatively, then the closer they are to knowing what speculative poetry is and is not. Clarke understood that, Asimov also, Heinlein did, and Elgin too. So go read the exemplars to which they’ve directed you already! Or you could do worse than perusing copies of the Star*Line print journal and Eye to the Telescope online journal, both curated by the SFPA.

As a final note, for this author, the nature of speculative poetry can (and should) never be entirely pinned down – the pinning itself would be to kill the butterfly, perhaps, a creature which is so much more beautiful when flying free. Any definition of speculative poetry is, by definition, too limited and limiting.

Dr Adam Dalton-West (author name A J Dalton)

London, UK, August 2025

Notes

1. Arthur C. Clarke, essay, “The Fantastic Muse”, Novae Terrae vol.2 no.11, May 1938.

2. Arthur C. Clarke, poem, “The Twilight of a Sun”, The Fantast vol.1 no.1, April 1939.

3. A J Dalton, essay, “Arthur C. Clarke’s Science Fiction Started With His Poetry”, Sci Phi Journal, June 2025, https://www.sciphijournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/SPJ-2025-02.pdf.

4. Neil Holford, essay, “The Big Three: Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein”, SFandFantasy.co.uk, 2011-2025, https://sfandfantasy.co.uk/php/the-big-3.php.

5. Robert Wilfred Franson, review, “The Green Hills of Earth by Robert A. Heinlein”, Troynovant, March 2005, https://www.troynovant.com/Atalanta/Bookcase-G/Heinlein-Robert-A/Green-Hills-of-Earth.html.

6. AIRBOYD, video, “Apollo 15 – In The Mountains Of The Moon (1971)”, YouTube, Dec 3, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xTGzesCsjs&t=1342s.

I really enjoyed reading this. Lots of good information on the history of modern speculative poetry.